REALLY SIMPLE rules for Mah-Jongg

THE TILES

Leave out the flowers (hey, you wanted SIMPLE rules, right?). Just use the basic 136 tiles:

DOTS (Numbered 1-9; 4 of each, for a total of 36)

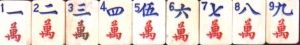

BAMS ("Sticks" numbered 1-9; the 1 looks like a bird; there are 4 of each, for a total of 36)  CRAKS (Chinese characters numbered 1-9; there are 4 of each, for a total of 36)

CRAKS (Chinese characters numbered 1-9; there are 4 of each, for a total of 36)

WINDS (Chinese characters labeled E, S, W, N; there are 4 of each, for a total of 16)

WINDS (Chinese characters labeled E, S, W, N; there are 4 of each, for a total of 16)

DRAGONS (Red Dragon, Green Dragon, White Dragon; there are 4 of each, for a total of 12; the whites may have a rectangular design or may be blank)

DRAGONS (Red Dragon, Green Dragon, White Dragon; there are 4 of each, for a total of 12; the whites may have a rectangular design or may be blank)

If you're not sure which tiles are which ("hey, is this what he's calling a white dragon, or is this a blank tile?"), don't worry about it! Just set up a 136-tile set and make sure everybody knows what's what for today. If you learn differently later, then adjust your thinking later. Mah-Jongg players have to be flexible!

SETTING UP THE GAME

4 people sit around a square table.

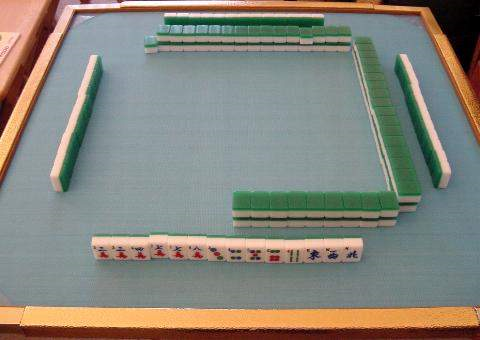

Turn all the tiles face down and mix'em all up real good. Now each player builds a wall (a row of tiles, 2 tiles high) 17 tiles long (each player makes a 34-tile wall). The 4 walls are set up like a square on the table. The ends of the walls do not need to touch one another.

The walls are 17 stacks long because the flowers are not used. When flowers are used, the walls are 18 stacks long. When 8 American jokers are used, the walls are 19 stacks long. But we're simplifying for this lesson, so don't use all them extra tiles! Just put them back in the box.

The walls are 17 stacks long because the flowers are not used. When flowers are used, the walls are 18 stacks long. When 8 American jokers are used, the walls are 19 stacks long. But we're simplifying for this lesson, so don't use all them extra tiles! Just put them back in the box.

There, that wasn't so bad, now, was it? You probably took longer to do that than you really needed to -- with a bit of practice it'll go faster. You have to do that at the start of each hand. You'll have more fun if everybody pitches in so it goes quickly and you don't get bogged down in the process of building walls.

Now choose who will be dealer. You can either let the host/hostess be the dealer, or everybody roll dice (high roller deals).

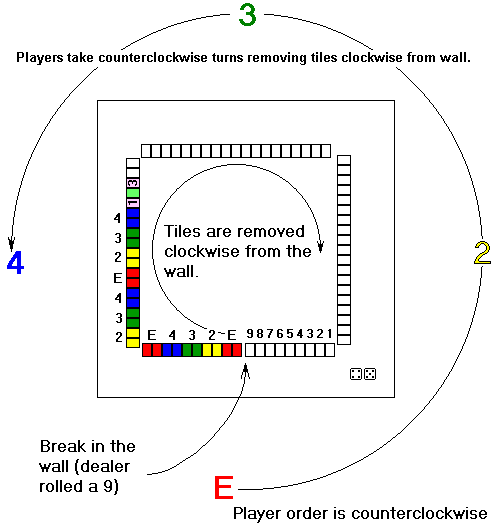

Dealer rolls 2 dice. Since these are simplified rules, we're going to do this the American way. Dealer counts the stacks in his/her wall, counting from the right to the left. If you roll 7, count 7 stacks (14 tiles).

After the last stack counted, break the wall. The tiles to the right of the break are the tiles you just counted. The deal begins from the left of the break. Players take turns counterclockwise, removing tiles clockwise from the wall. See the picture.

Dealer takes 2 stacks (4 tiles).

Player to dealer's right takes the next 2 stacks (taking next 2 stacks to dealer's left).

Player across from the dealer takes the next 2 stacks.

Going counterclockwise around the table, each player in turn removes tiles in clockwise order from the wall. There are two directions happening simultaneously - counterclockwise (the players taking tiles in turn) and clockwise (the tiles disappearing from the wall). During the course of play, players always take turns counterclockwise (even during the deal) - and tiles are always removed clockwise from the wall (even during the deal).

Keep on going like that until every player has taken 6 stacks (12 tiles). (Quickly now! Don't take too long, or the game will seem tedious and complicated.)

Dealer takes one tile from the end of the wall (top of last stack).

Player to dealer's right takes the tile under that.

Player across from dealer takes one tile from end of the wall (top of last stack).

Player to dealer's left takes the tile under that.

Dealer takes one more tile -- from end of wall (top of last stack).

(Note: the procedure I just described varies slightly from the way players customarily do this -- I just made it a little simpler.)

The setup phase is now completed.

Dealer now has 14 tiles.

Every other player now has 13 tiles.

Stand up your tiles on end in front of you, in a neat straight line with no gaps. (Or if you have racks, lean them on the sloped surface facing you.) The tiles should face you only -- you don't want the other players to see what you have.

Organize your tiles by suit and by number value. Do not make gaps between groupings. Neat straight line.

Now you're ready to play mah-jongg.

THE GOAL OF CHINESE MAH-JONGG

The goal of the game is to go out with a complete mah-jongg hand before anybody else does. It's a lot like the card game "Rummy."

WHAT'S A COMPLETE MAH-JONGG HAND?

A complete 14-tile mah-jongg hand is comprised of FOUR GROUPS AND A PAIR.

A PAIR, of course, is two identical tiles. Each GROUP in the hand is three tiles, so the total in a complete hand (four groups and a pair) is fourteen tiles.

WHAT'S A GROUP OF TILES?

There are two kinds of groups: "pungs" and "chows." (For the purpose of simplification, these rules ignore the group called a "kong.")

A PUNG is three identical tiles (a "triplet" or "triple"). For example, if you have a Two Dot tile, and another, and another, you have a "pung" of Two Dots. Unlike playing cards and Rummy, you cannot make a group with a Two in one suit, a Two in another suit, and a Two in a third suit. (You can do that in certain hands in Western mah-jongg, but not in Chinese mah-jongg.)

Two example pungs: a pung of Green Dragons and a pung of Four Dots.

Two example pungs: a pung of Green Dragons and a pung of Four Dots.

A CHOW is three tiles in a row (a "sequence" or "run"). For example, if you have a Six Bam and a Seven Bam and an Eight Bam. You cannot make a chow with tiles in different suits (they must all be in the same suit). And you cannot make a chow with Dragons or Winds (the tiles in a chow must be numbered suit tiles).

Two example chows: a 123 of Craks, and a 678 of Bams.

Two example chows: a 123 of Craks, and a 678 of Bams.

Here is an example hand:

An example hand comprised of: a pung (dragon), a chow (craks), a pung (dots), a chow (bams), and a pair (winds).

An example hand comprised of: a pung (dragon), a chow (craks), a pung (dots), a chow (bams), and a pair (winds).

A hand does not have to be two chows, two pungs, and a pair (as in the example above). It can be four pungs and a pair, or four chows and a pair, or three chows and a pung and a pair... get the idea? Any four groups and a pair.

NOTE (do not read this if you are not ready to deal with fine points): To be entirely accurate, "pung" is a verb meaning "I claim that tile to make a triplet." Thus the noun for "group of three identical tiles" is "triplet." Pung = verb. Triplet = noun. But this will only be an issue when playing with a purist or someone who speaks Chinese.

HOW DO YOU PLAY?

When we left our brave little troupe of players at the end of our last episode, the deal had just occurred. The dealer had 14 tiles and everybody else had 13 tiles.

So, to begin, it's the dealer's turn. The dealer examines the tiles in his/her hand to see if his/her hand is already a winner or not. Is the hand composed of four groups and a pair? If so, dealer wins instantly. (That is a rare occurrence. If dealer wins on initial deal, all players must gesticulate to heaven and exclaim "oh my gosh!" three times.) If dealer's hand is not yet composed of four groups and a pair, dealer must discard a tile.

Important note for the dealer (or for any player): if you find any completed groups in your hand, keep them concealed in your hand. Do NOT expose them face-up on the table. And don't space them apart from your other tiles. Keep your concealed groupings a secret from your opponents.

HOW DO I CHOOSE A TILE TO DISCARD?

Just pick a tile that does not look like it goes with anything else, and throw it away. The purpose of this writeup is to give simplified rules, not in-depth strategy. You can learn strategy later, after you master the basics.

DISCARDING

Dealer must take any one tile from the hand and place it face-up in the center of the table (between the walls). Dealer now has 13 tiles in the hand. Dealer's turn is now over.

And now there's a discard on the table.

CAN I TAKE SOMEONE ELSE'S DISCARD?

It sometimes happens that a player's discarded tile helps complete your hand. When that happens, YES, you can take it. This move is only allowed under special circumstances, however...

You can only take the tile discarded by the most recent player. If there are 5 or 6 tiles lying in the center of the table, only the newest one is up for grabs. And it is only available (the "window of opportunity" is only open) for a few seconds until the next player makes a move. You have to be quick in mah-jongg!

Unlike some Rummy rules, you cannot take a discard and place it in your hand. You are only allowed to take someone's discard if it completes a three-tile grouping, or if it completes the hand.

TAKING A DISCARD TO MAKE A CHOW (RUN)

To take a discard to make a CHOW (a run, like 1-2-3): You may only make a chow on your own turn (you may only take a discard to make a chow when it is discarded by the player whose turn goes just before yours, in orderly play going around the table).

For example: IF the dealer (player #1) discards a Three Crak, and you are holding a Four Crak and a Five Crak, AND you are the next player to the right (you are player #2), THEN you can claim the discard.

When you take a discard to make a chow, you must verbalize the action. Normally, folks say "chow," but if you're a beginner and are having trouble remembering the term "chow," then just use the American practice, and say "I'll take that" or "Ooh! I want that!" or something. (See "After Taking A Discard," below.)

TAKING A DISCARD TO MAKE A PUNG (TRIPLET)

To take a discard to make a PUNG (a triplet, like E-E-E): You may take the discard instantly when it appears on the table, regardless of whose turn it is. If you have a pair of East Winds, and somebody discards a third East Wind, you are allowed to claim it even if it's not your turn. Say "pung" or "I want that," and take it immediately. (See "After Taking A Discard," below.)

TAKING A DISCARD TO WIN THE HAND (MAH-JONGG)

To take a discard to WIN THE HAND (to make a complete "four groups and a pair" configuration): You may take the discard instantly when it appears on the table, regardless of whose turn it is. If your hand is complete except for one tile, and that tile is discarded, you are allowed to claim it even if it's not your turn. Say "mah-jongg," and take it immediately. (See "Somebody Wins," below.)

Note: you can never take a discard to expose a PAIR by itself. You can take a discard to complete a pair only when you already have four complete three-tile groupings (i.e., when completing the pair completes the hand).

AFTER TAKING A DISCARD

There is a price you must pay for taking a discard -- you have to expose the completed grouping. Never take a discarded tile and place it in your hand. Take it from its face-up position in the center of the table and bring it in front of your hand. Place the rest of the tiles of the grouping face-up beside it, so everybody can see what grouping you have made. This exposed grouping goes between your hand and the wall (not between your hand and the edge of the table). If you use American-style racks, place the exposed grouping on the shelf atop the rack.

After exposing the completed grouping, if you did not win, you have to discard a tile. (Be quick about it so the game can move on.)

If you took a discard to make a pung, the player to your right goes next. It's possible to skip a player's turn when someone makes a pung. Don't get all bent out of shape about it if your turn is skipped this way. Them's the rules!

INSTEAD OF TAKING A DISCARD

Above, we have considered what would happen if the dealer's first discard was useful to someone. Usually, it isn't. When Player 2 cannot use the tile discarded by the dealer, Player 2 would just draw from the end of the wall. Remember how we took tiles in the deal? Keep going clockwise around the wall when picking tiles. Player 2 now has 14 tiles. If the hand is not a complete "4 groups and a pair" yet, Player 2 must discard.

Try to think ahead what tile you will discard on your next turn so the game will progress quickly. The game is more fun if it moves smoothly and quickly.

NEXT PLAYER'S TURN

Play progresses counter-clockwise around the table in mah-jongg. On your turn, you start with 13 tiles. Then you take a 14th tile into your hand (usually by picking it from the wall; sometimes you take a discard and expose a grouping). If your hand is not yet complete (it usually isn't), you discard a tile. Now you have 13 tiles again. That's the way a typical turn works. Then it's the next player's turn.

AND SO ON.

Until...

THE HAND IS OVER.

There are two ways the hand can end: either somebody wins, or nobody wins.

SOMEBODY WINS

The moment someone has a hand of 14 tiles, with four groups and a pair, that player wins. Let's say it's you. Let's say you have a pung of West Winds, a one-two-three of Dots, a five-six-seven of Bams, a pung of Eight Craks, and a pair of Nine Dots.

WWW d123 b567 c888 d99

Immediately say, "Mah-Jongg!" Lie all your tiles down on the table, face-up. (If you use racks, place them on the top shelf of the rack.) You have won the hand. Everybody stops playing while the score is tabulated.

NOBODY WINS

The moment there are no more tiles left in the wall, nobody can continue playing. It's a wall game. Everybody throw in your tiles and shuffle them good. Build new walls and go again. (See "Who Deals Next?," below.)

SCORING THE HAND

Scoring Chinese mah-jongg is usually called "too complicated," so don't bother with it until you've mastered all these basics.

Just do it this way:

- Whoever won gets a chip or a coin from everybody.

- Or just use the "ooh and aah" method. When somebody wins, everybody goes "ooh."

- You can keep track of score on a piece of paper too. Make a tick mark next to the winner's name.

Whatever works for you.

If you want to make things really exciting, award an extra chip, coin, or "aah" for a pung of dragons or winds.

If you want to recognize dragon or wind pungs for all players (not only for the player who goes mah-jongg), you can do that. It might be possible for a non-winning player to get a higher score than a winner, if you allow this. But that's OK, if you like it that way.

(If you want to learn how to REALLY score Chinese mah-jongg, go get a good website or book about Chinese mah-jongg (see FAQ 4b for websites, see FAQ 3 for books). It's recommended you don't expose yourself to "real" mah-jongg scoring until you have mastered all the basics described in this writeup.)

WHO DEALS NEXT?

After a hand has ended, you have to determine whether the deal moves on or not. If the rest of this sounds too complicated, just give the dice to the next player and keep the deal moving (the way they do it in American mah-jongg, and the new official Chinese rules). But here's the way it works in most Asian forms of mah-jongg:

If the dealer wins, the dealer keeps the deal. If it's a wall game, the dealer keeps the deal. Otherwise, the deal moves on to the next player (Player 2).

GAME STRUCTURE

In American mah-jongg, each hand is a complete "game" unto itself. You just keep playing until a pre-agreed time, or until somebody gets tired. You can use this structure if you want.

In Chinese mah-jongg, the deal moves completely around the table four times. Each player is dealer four times. To use this method, you have to keep track of who the first dealer was, and how many times the deal has been around the table. Use any tracking method you like. I don't want to complicate things by describing the way it's really done.

In Japanese mah-jongg, the deal moves completely around the table twice.

You can use any of the above game structures you like. Or you can set it up to work however you want (maybe you play until someone wins a total of 20 chips or coins, or whatever).

RESOLVING CONFLICTS

It is normal and expected that something will happen in a mah-jongg game in which a conflict has to be resolved.

If two players both want to take a discard, there are clear rules as to which player can take it. (See "Conflicting Claims," below.)

If players have conflicting ideas about how a rule should be interpreted, then just try to resolve it harmoniously for the moment and keep the game moving. You can always find out the real rule before the next play session. If you resolved it harmoniously the first time, you might well WANT to play together again! Take a vote. If 3 players interpret a rule one way, and 1 player another, then go with the majority. If it's split 2 and 2, then flip a coin for the time being. Don't get all bent out of shape about a rule interpretation. Be nice and have fun together. (For more about this, see "More Thoughts On Resolving Conflicts," below.)

CONFLICTING CLAIMS

When one player wants a discard to make a chow, and one wants it to make a pung, then the punger gets the tile (claims for a pung outprioritize claims for a chow).

When one player wants a discard to make a pung, and another player wants it for a win, then the winner gets the tile (claims for a win outprioritize claims for a pung).

When two players both want a discard to win, then the player first in line gets the win. Let's say Player 1 throws a tile, and Player 3 and Player 4 both want it. Player 3's turn would normally come before Player 4's turn, so Player 3 wins this conflict.

When two players both want a discard to make a chow, then something's wrong. Somebody didn't understand the rule where it says that only the player to the discarder's right can claim a chow.

When two players both want a discard to make a pung, then something's wrong. There are only 4 of each tile! (In American mah-jongg, there are jokers, so it is possible for such a conflict in that game, but in Chinese mah-jongg there usually are no jokers. If you do use jokers, then the player first in line gets the tile.)

MORE THOUGHTS ON RESOLVING CONFLICTS

Resolving conflicts often involves perpetrating an unavoidable unfairness (or a perceived unfairness) on someone. Seek the smallest unfairness to the smallest number of players.

When ruling on conflicts arising out of someone's error, first determine who made the error. If you make a mistake, you are the one who should suffer its consequences, not everybody else at the table. You can ask for, but not demand, a second chance. There is no rule that says, "mistakes must be forgiven by the other players."

How to decide when mistakes may (or must) be taken back:

a. When a player makes a mistake that messes up her own hand, and realizes it immediately (before discarding a tile, thus ending her turn), it is not too late to rectify the error. Do it now!

b. When a player makes a mistake that messes up her own hand, and realizes it after discarding, then it's too late, and she must live with the mistake.

c. When a player makes a mistake that messes up the game, and it is realized immediately, the mistake must be rectified on the spot.

d. When a player makes a mistake that messes up the game, and it is not realized immediately (thus cannot be rectified), it is best for all players to just throw in their hands and start over.

Harmony is more important than winning. If a conflict was ruled against you -- or if your request for a chance to do something over was turned down -- or if you had to throw in a potentially great hand because of someone else's error, then accept it graciously and move on. And no grousing about it later. You want to play again another day, right? That means you want others to enjoy playing with you. If all you care about is winning, nobody will want to play with you. Good gamesmanship is about much more than just winning. It's about getting along, too.

Numbers

一 (yī) “one”

二 (èr) “two”

三 (sān) “three”

四 (sì) “four”

五 (wǔ) “five”

六 (liù) “six”

七 (qī) “seven”

八 (bā) “eight”

九 (jiǔ) “nine”

General

洗牌 (xǐpái) “shuffle tiles (or cards)”

出牌 (chūpái) “play a tile”

摸牌 (mōpái) “draw a tile”

和了 (húle) “I’ve won!”

吃 (chī) said when you take a tile to complete a straight

碰 (pèng) said when you take a tile to complete a set of three

槓 (gàng) said when you take a tile to complete a set of four

Tiles

筒 (tǒng) “circle (suite)”

条/條 (tiáo) “bamboo (suite)”

万/萬 (wàn) “characters (suite)”

东风/東風 (dōngfēng) “east wind”

南风/南風 (nánfēng) “south wind”

西风西風 (xīfēng) “west wind”

北風 (běifēng) “north wind”

红/紅中 (hóngzhōng) “red dragon” (lit. “red centre”)

发财/發財 (fācái) “green dragon” (lit. “make a fortune”)

白板 (báibǎn) “white dragon” (lit. “white board/slate”)